I had an interesting discussion with some folks last night. The question was whether it is possible for all investments to go down in the short term if things get bad enough. One conclusion was that it’s a harder question to answer than you might think. Do you consider perceived value, or just market price? If you buy a farm, and the market collapses for real estate, that farm might still be the best thing you’ve ever bought (high value), even if the price plummets. So, while the general question is interesting philosophically, it quickly unravels into a debate on definitions, so I’ll just limit the discussion to what people normally think of as investments: things you can hold in a brokerage account.

My theory is that it is certainly possible for every conceivable investment to lose value, where no matter if you’re short or long you lose money. Just consider the absurd case where everybody becomes clinically depressed agoraphobics, sitting at home wasting away. Clearly, financial markets will freeze, and you’ll find out that your assumptions on value were predicated on the Wall Street showing up to work, the computers which record your trades running, and people holding out enough hope in the future to bother trading anything but cigarettes. Every asset, no matter what, has some finite counterparty risk. You may be right about everything, but the universe doesn’t owe you a bid. There probably weren’t a lot of good places to put your retirement funds during the declining Roman Empire, for example.

Granted, total collapse of financial market functioning is a rather extreme, and seemingly academic, case to consider. But as I thought about it a bit more after the discussion, I realized that this isn’t academic at all. Between fully liquid bull markets, where everybody makes money (on paper) and the macabre situation I posited above, is a continuum of completely plausible scenarios where it gets harder and harder to make money in any asset. In fact, this is already happening right now.

Bid-ask spreads on options have been widening in the past few months, which makes it harder to hedge either direction as liquidity dries up. While derivative markets are zero sum if you average out to expiration, in the short term both parties can have losses on paper due to wide spreads, and if you can’t close your short option position, you are forced to tie up cash as collateral, which could cause you to lose money. Thus, in a way both parties to an option contract can lose out if liquidity dries up.

Certain stocks are becoming impossible to short (nobody is willing to loan out any more shares). Others (such as Sears) are starting to require short holders to pay interest. It’s quite likely for somebody to go long Sears, somebody else to go short at the same time, and for both people to lose money.

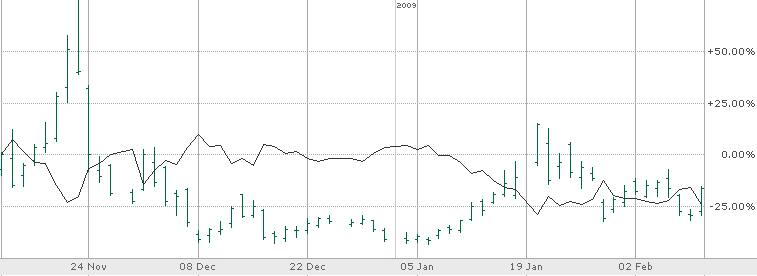

Is this discussion of any practical value? I think so: if the market continues to deteriorate, even those that correctly predict it will have trouble making money from it. For example, it will become increasingly difficult to make money in inverse ETFs, no matter how brilliantly you predict the underlying stock market trends. The counterparties to the derivatives owned by the ETF will become so adverse to risk that they will insist upon prices which are less and less favorable for the ETF. This will manifest as extreme slippage in the ETF relative to the index it inversely tracks. Again, this is already happening. Consider the following plot of SKF versus the Dow Financials Index, which it is supposed to track the inverse of times two:

The underlying index went down about 25%, but so did the ETF (there were no distributions from SKF in this time frame). Everybody lost money, long or short! Some slippage is inevitable as a “cost” of leverage and shorting, but my point is that the slippage is getting worse. Six months ago SKF was tracking much closer to its target. It might be useful to consider an index of inverse ETF slippage as an indicator of the health of the financial markets, or at the very least a index of how crazy you’d have to be to remain in the market. So, the ETF slippage, the option spreads, tight short supply: they might all be subtle hints from the market that the market is no place to be right now, long or short.

One response to “Investment gains may become harder to find, long or short.”

It’s a very nice blog. Nice to meet you. Salam from Indonesia.